A small tribute to the works of valuable composers, musicians, players and poets. From Al Green and Alberta Hunter to Zoot Sims and Shemekia Copeland, among many others. Covering songs from styles as different as bluegrass, blues, classical, country, heavy metal, jazz, progressive, rock and soul music.

Showing posts with label Acoustic blues. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Acoustic blues. Show all posts

Friday, 6 January 2012

Bukka White "The Panama limited" (1971)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

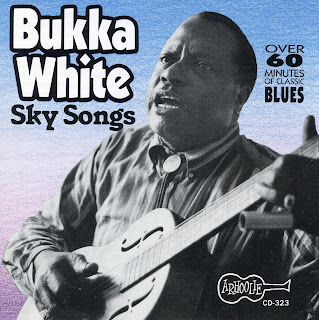

Bukka White "Sky songs" (1965)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

Bukka White "1963 isn't 1962" (1963)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

Bukka White "The complete sessions" (1930-40)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

Bukka White

Bukka White

(true name: Booker T. Washington White) was born in Houston,

Mississippi (not Houston, Texas) in 1906 (not any date between 1902-1905

or 1907-1909, as is variously reported). He got his initial start in

music learning fiddle tunes from his father. Guitar instruction soon

followed, but White's

grandmother objected to anyone playing "that Devil music" in the

household; nonetheless, his father eventually bought him a guitar. When Bukka White

was 14 he spent some time with an uncle in Clarksdale, Mississippi and

passed himself off as a 21-year-old, using his guitar playing as a way

to attract women. Somewhere along the line, White came in contact with Delta blues legend Charley Patton, who no doubt was able to give Bukka White instruction on how to improve his skills in both areas of endeavor. In addition to music, White pursued careers in sport, playing in Negro Leagues baseball and, for a time, taking up boxing.

In 1930 Bukka White met furniture salesman Ralph Limbo, who was also a talent scout for Victor. White traveled to Memphis where he made his first recordings, singing a mixture of blues and gospel material under the name of Washington White. Victor only saw fit to release four of the 14 songs Bukka White recorded that day. As the Depression set in, opportunity to record didn't knock again for Bukka White until 1937, when Big Bill Broonzy asked him to come to Chicago and record for Lester Melrose. By this time, Bukka White had gotten into some trouble -- he later claimed he and a friend had been "ambushed" by a man along a highway, and White shot the man in the thigh in self defense. While awaiting trial, White jumped bail and headed for Chicago, making two sides before being apprehended and sent back to Mississippi to do a three-year stretch at Parchman Farm. While he was serving time, White's record "Shake 'Em on Down" became a hit.

Bukka White proved a model prisoner, popular with inmates and prison guards alike and earning the nickname "Barrelhouse." It was as "Washington Barrelhouse White" that White recorded two numbers for John and Alan Lomax at Parchman Farm in 1939. After earning his release in 1940, he returned to Chicago with 12 newly minted songs to record for Lester Melrose. These became the backbone of his lifelong repertoire, and the Melrose session today is regarded as the pinnacle of Bukka White's achievements on record. Among the songs he recorded on that occasion were "Parchman Farm Blues" (not to be confused with "Parchman Farm" written by Mose Allison and covered by John Mayall's Bluesbreakers and Blue Cheer, among others), "Good Gin Blues," "Bukka's Jitterbug Swing," "Aberdeen, Mississippi Blues," and "Fixin' to Die Blues," all timeless classics of the Delta blues. Then, Bukka disappeared -- not into the depths of some Mississippi Delta mystery, but into factory work in Memphis during World War II.

Bob Dylan recorded "Fixin' to Die Blues" on his 1961 debut Columbia album, and at the time no one in the music business knew who Bukka White was -- most figured a fellow who'd written a song like "Fixin' to Die" had to be dead already. Two California-based blues enthusiasts, John Fahey and Ed Denson, were more skeptical about this assumption, and in 1963 addressed a letter to "Bukka White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi." By chance, one of White's relatives was working in the Post Office in Aberdeen, and forwarded the letter to White in Memphis.

Things moved quickly from the time Bukka White met up with Fahey and Denson; by the end of 1963 Bukka White was already recording on contract with Chris Strachwitz and Arhoolie. White wrote a new song celebrating his good fortune entitled "1963 Isn't 1962 Blues" and swiftly recorded three albums of material for Strachwitz which the latter entitled Sky Songs, referring to White's habit of "reaching up and pulling songs out of the sky." Nonetheless, even White knew he couldn't get away with making up all his material regularly in performance, so he also studied his 78s and relearned all the songs he'd written for Lester Melrose. Although Bukka White was practically the same age as other survivors of the Delta and Memphis blues scenes of the 1920s and '30s, he didn't look like someone who belonged in a nursing home. White was a sharp dresser, in the prime of health, was a compelling entertainer and raconteur, and clearly enjoyed being the center of attention. He thrived on the folk festival and coffeehouse circuit of the 1960s.

By the '70s, however, Bukka White couldn't help getting a little bored with his celebrity status as an acoustic bluesman. White's tastes had grown with the times, and he would have loved to have played an electric guitar and fronted a band, as his old acquaintance Chester Burnett (aka Howlin' Wolf) and Bukka's own cousin, B. B. King, had been already doing successfully for years. But he only needed to look at what happened to his friend Bob Dylan's career for a lesson on what happens to folk blues artists who try and "go electric." So, Bukka White stayed on the festival circuit to the end of his days, beating the hell out of his National steel guitar, and sometimes his monologues would go on a little long, and sometimes his playing was a little more willfully eccentric than at others. Patrons would wait patiently to hear Bukka play "Parchman Farm Blues," although some of them were under the mistaken impression that they had paid their money to hear an artist who had originated a number that Eric Clapton made famous.

Blues purists will tell you that nothing Bukka White recorded after 1940 is ultimately worth listening to. This isn't accurate, nor fair. White was an incredibly compelling performer who gave up of more of himself in his work than many artists in any musical discipline. The Sky Songs albums for Arhoolie are an eminently rewarding document of Bukka's charm and candor, particularly in the long monologue "Mixed Water." "Big Daddy," recorded in 1974 for Arnold S. Caplin's Biograph label, likewise is a classic of its kind and should not be neglected.

Source: All Music.com.

In 1930 Bukka White met furniture salesman Ralph Limbo, who was also a talent scout for Victor. White traveled to Memphis where he made his first recordings, singing a mixture of blues and gospel material under the name of Washington White. Victor only saw fit to release four of the 14 songs Bukka White recorded that day. As the Depression set in, opportunity to record didn't knock again for Bukka White until 1937, when Big Bill Broonzy asked him to come to Chicago and record for Lester Melrose. By this time, Bukka White had gotten into some trouble -- he later claimed he and a friend had been "ambushed" by a man along a highway, and White shot the man in the thigh in self defense. While awaiting trial, White jumped bail and headed for Chicago, making two sides before being apprehended and sent back to Mississippi to do a three-year stretch at Parchman Farm. While he was serving time, White's record "Shake 'Em on Down" became a hit.

Bukka White proved a model prisoner, popular with inmates and prison guards alike and earning the nickname "Barrelhouse." It was as "Washington Barrelhouse White" that White recorded two numbers for John and Alan Lomax at Parchman Farm in 1939. After earning his release in 1940, he returned to Chicago with 12 newly minted songs to record for Lester Melrose. These became the backbone of his lifelong repertoire, and the Melrose session today is regarded as the pinnacle of Bukka White's achievements on record. Among the songs he recorded on that occasion were "Parchman Farm Blues" (not to be confused with "Parchman Farm" written by Mose Allison and covered by John Mayall's Bluesbreakers and Blue Cheer, among others), "Good Gin Blues," "Bukka's Jitterbug Swing," "Aberdeen, Mississippi Blues," and "Fixin' to Die Blues," all timeless classics of the Delta blues. Then, Bukka disappeared -- not into the depths of some Mississippi Delta mystery, but into factory work in Memphis during World War II.

Bob Dylan recorded "Fixin' to Die Blues" on his 1961 debut Columbia album, and at the time no one in the music business knew who Bukka White was -- most figured a fellow who'd written a song like "Fixin' to Die" had to be dead already. Two California-based blues enthusiasts, John Fahey and Ed Denson, were more skeptical about this assumption, and in 1963 addressed a letter to "Bukka White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi." By chance, one of White's relatives was working in the Post Office in Aberdeen, and forwarded the letter to White in Memphis.

Things moved quickly from the time Bukka White met up with Fahey and Denson; by the end of 1963 Bukka White was already recording on contract with Chris Strachwitz and Arhoolie. White wrote a new song celebrating his good fortune entitled "1963 Isn't 1962 Blues" and swiftly recorded three albums of material for Strachwitz which the latter entitled Sky Songs, referring to White's habit of "reaching up and pulling songs out of the sky." Nonetheless, even White knew he couldn't get away with making up all his material regularly in performance, so he also studied his 78s and relearned all the songs he'd written for Lester Melrose. Although Bukka White was practically the same age as other survivors of the Delta and Memphis blues scenes of the 1920s and '30s, he didn't look like someone who belonged in a nursing home. White was a sharp dresser, in the prime of health, was a compelling entertainer and raconteur, and clearly enjoyed being the center of attention. He thrived on the folk festival and coffeehouse circuit of the 1960s.

By the '70s, however, Bukka White couldn't help getting a little bored with his celebrity status as an acoustic bluesman. White's tastes had grown with the times, and he would have loved to have played an electric guitar and fronted a band, as his old acquaintance Chester Burnett (aka Howlin' Wolf) and Bukka's own cousin, B. B. King, had been already doing successfully for years. But he only needed to look at what happened to his friend Bob Dylan's career for a lesson on what happens to folk blues artists who try and "go electric." So, Bukka White stayed on the festival circuit to the end of his days, beating the hell out of his National steel guitar, and sometimes his monologues would go on a little long, and sometimes his playing was a little more willfully eccentric than at others. Patrons would wait patiently to hear Bukka play "Parchman Farm Blues," although some of them were under the mistaken impression that they had paid their money to hear an artist who had originated a number that Eric Clapton made famous.

Blues purists will tell you that nothing Bukka White recorded after 1940 is ultimately worth listening to. This isn't accurate, nor fair. White was an incredibly compelling performer who gave up of more of himself in his work than many artists in any musical discipline. The Sky Songs albums for Arhoolie are an eminently rewarding document of Bukka's charm and candor, particularly in the long monologue "Mixed Water." "Big Daddy," recorded in 1974 for Arnold S. Caplin's Biograph label, likewise is a classic of its kind and should not be neglected.

Source: All Music.com.

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

Saturday, 19 November 2011

Blind Boy Fuller "Remastered 1935-38" (2004)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues,

Country blues,

East coast blues,

Folk-blues,

Piedmont blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Regional blues

Blind Boy Fuller

Blind Boy Fuller (born Fulton Allen) (July 10, 1907 – February 13, 1941) was an American blues guitarist and vocalist. He was one of the most popular of the recorded Piedmont blues artists with rural Black Americans, a group that also included Blind Blake, Josh White, and Buddy Moss.

LIFE AND CAREER

Fulton Allen was born in Wadesboro, North Carolina, United States, to Calvin Allen and Mary Jane Walker. He was one of a family of 10 children, but after his mother's death he moved with his father to Rockingham. As a boy he learned to play the guitar and also learned from older singers the field hollers, country rags, and traditional songs and blues popular in poor, rural areas.

He married Cora Allen young and worked as a labourer, but began to lose his eyesight in his mid-teens. According to researcher Bruce Bastin, "While he was living in Rockingham he began to have trouble with his eyes. He went to see a doctor in Charlotte who allegedly told him that he had ulcers behind his eyes, the original damage having been caused by some form of snow-blindness." However, there is an alternative story that he was blinded by an ex-girlfriend who threw chemicals in his face.

By 1928 he was completely blind, and turned to whatever employment he could find as a singer and entertainer, often playing in the streets. By studying the records of country blues players like Blind Blake and the "live" playing of Gary Davis, Allen became a formidable guitarist, and played on street corners and at house parties in Winston-Salem, NC, Danville, VA, and then Durham, North Carolina. In Durham, playing around the tobacco warehouses, he developed a local following which included guitarists Floyd Council and Richard Trice, as well as harmonica player Saunders Terrell, better known as Sonny Terry, and washboard player/guitarist George Washington.

In 1935, Burlington record store manager and talent scout James Baxter Long secured him a recording session with the American Recording Company (ARC). Allen, Davis and Washington recorded several tracks in New York City, including the traditional "Rag, Mama, Rag". To promote the material, Long decided to rename Allen as "Blind Boy Fuller", and also named Washington Bull City Red.

Over the next five years Fuller made over 120 sides, and his recordings appeared on several labels. His style of singing was rough and direct, and his lyrics explicit and uninhibited as he drew from every aspect of his experience as an underprivileged, blind Black person on the streets—pawnshops, jailhouses, sickness, death—with an honesty that lacked sentimentality. Although he was not sophisticated, his artistry as a folk singer lay in the honesty and integrity of his self-expression. His songs contained desire, love, jealousy, disappointment, menace and humor.

In April 1936, Fuller recorded ten solo performances, and also recorded with guitarist Floyd Council. The following year, after auditioning for J. Mayo Williams, he recorded for the Decca label, but then reverted to ARC. Later in 1937, he made his first recordings with Sonny Terry. In 1938 Fuller, who was described as having a fiery temper, was imprisoned for shooting a pistol at his wife, wounding her in the leg, causing him to miss out on John Hammond's "From Spirituals to Swing" concert in NYC that year. While Fuller was eventually released, it was Sonny Terry who went in his stead, the beginning of a long "folk music" career. Fuller's last two recording sessions took place in New York City during 1940.

Fuller's repertoire included a number of popular double entendre "hokum" songs such as "I Want Some Of Your Pie", "Truckin' My Blues Away" (the origin of the phrase "keep on truckin'"), and "Get Your Yas Yas Out" (adapted as "Get Your Ya-Yas Out" for the origin of a later Rolling Stones album title), together with the autobiographical "Big House Bound" dedicated to his time spent in jail. Though much of his material was culled from traditional folk and blues numbers, he possessed a formidable finger-picking guitar style. He played a steel National resonator guitar. He was criticised by some as a derivative musician, but his ability to fuse together elements of other traditional and contemporary songs and reformulate them into his own performances, attracted a broad audience. He was an expressive vocalist and a masterful guitar player, best remembered for his uptempo ragtime hits including "Step It Up and Go". At the same time he was capable of deeper material, and his versions of "Lost Lover Blues", "Rattlesnakin' Daddy" and "Mamie" are as deep as most Delta blues. Because of his popularity, he may have been overexposed on records, yet most of his songs remained close to tradition and much of his repertoire and style is kept alive by other Piedmont artists to this day.

DEATH

Fuller underwent a suprapubic cystostomy in July 1940 (probably an outcome of excessive drinking) but continued to require medical treatment. He died at his home in Durham, North Carolina on February 13, 1941 at 5:00 PM of pyemia due to an infected bladder, GI tract and perineum, plus kidney failure.

He was so popular when he died that his protégé Brownie McGhee recorded "The Death of Blind Boy Fuller" for the Okeh label, and then reluctantly began a short lived career as Blind Boy Fuller No. 2 so that Columbia Records could cash in on his popularity.

BURIAL LOCATION

Blind Boy Fuller's final resting place is Grove Hill Cemetery, located on private property in Durham, North Carolina. State records indicate that this was once an official cemetery, and Fuller's interment is recorded. The only remaining headstone is that of Mary Caston Langey. The funeral arrangements were handled by McLaurin Funeral Home of Durham, North Carolina, and the burial took place on February 15, 1941.

Blind Boy Fuller has been recognized on two different plaques in the City of Durham. The North Carolina Division of Archives and History plaque is located a few miles north of Fuller's gravesite, along Fayetteville St. in Durham. The City of Durham officially recognized Fuller on July 16, 2001, and the commemorating plaque is located along the American Tobacco Trail, adjacent to the property where Fuller's unmarked grave is located (several hundred feet east of Fayetteville St.).

Source: Wikipedia.

LIFE AND CAREER

Fulton Allen was born in Wadesboro, North Carolina, United States, to Calvin Allen and Mary Jane Walker. He was one of a family of 10 children, but after his mother's death he moved with his father to Rockingham. As a boy he learned to play the guitar and also learned from older singers the field hollers, country rags, and traditional songs and blues popular in poor, rural areas.

He married Cora Allen young and worked as a labourer, but began to lose his eyesight in his mid-teens. According to researcher Bruce Bastin, "While he was living in Rockingham he began to have trouble with his eyes. He went to see a doctor in Charlotte who allegedly told him that he had ulcers behind his eyes, the original damage having been caused by some form of snow-blindness." However, there is an alternative story that he was blinded by an ex-girlfriend who threw chemicals in his face.

By 1928 he was completely blind, and turned to whatever employment he could find as a singer and entertainer, often playing in the streets. By studying the records of country blues players like Blind Blake and the "live" playing of Gary Davis, Allen became a formidable guitarist, and played on street corners and at house parties in Winston-Salem, NC, Danville, VA, and then Durham, North Carolina. In Durham, playing around the tobacco warehouses, he developed a local following which included guitarists Floyd Council and Richard Trice, as well as harmonica player Saunders Terrell, better known as Sonny Terry, and washboard player/guitarist George Washington.

In 1935, Burlington record store manager and talent scout James Baxter Long secured him a recording session with the American Recording Company (ARC). Allen, Davis and Washington recorded several tracks in New York City, including the traditional "Rag, Mama, Rag". To promote the material, Long decided to rename Allen as "Blind Boy Fuller", and also named Washington Bull City Red.

Over the next five years Fuller made over 120 sides, and his recordings appeared on several labels. His style of singing was rough and direct, and his lyrics explicit and uninhibited as he drew from every aspect of his experience as an underprivileged, blind Black person on the streets—pawnshops, jailhouses, sickness, death—with an honesty that lacked sentimentality. Although he was not sophisticated, his artistry as a folk singer lay in the honesty and integrity of his self-expression. His songs contained desire, love, jealousy, disappointment, menace and humor.

In April 1936, Fuller recorded ten solo performances, and also recorded with guitarist Floyd Council. The following year, after auditioning for J. Mayo Williams, he recorded for the Decca label, but then reverted to ARC. Later in 1937, he made his first recordings with Sonny Terry. In 1938 Fuller, who was described as having a fiery temper, was imprisoned for shooting a pistol at his wife, wounding her in the leg, causing him to miss out on John Hammond's "From Spirituals to Swing" concert in NYC that year. While Fuller was eventually released, it was Sonny Terry who went in his stead, the beginning of a long "folk music" career. Fuller's last two recording sessions took place in New York City during 1940.

Fuller's repertoire included a number of popular double entendre "hokum" songs such as "I Want Some Of Your Pie", "Truckin' My Blues Away" (the origin of the phrase "keep on truckin'"), and "Get Your Yas Yas Out" (adapted as "Get Your Ya-Yas Out" for the origin of a later Rolling Stones album title), together with the autobiographical "Big House Bound" dedicated to his time spent in jail. Though much of his material was culled from traditional folk and blues numbers, he possessed a formidable finger-picking guitar style. He played a steel National resonator guitar. He was criticised by some as a derivative musician, but his ability to fuse together elements of other traditional and contemporary songs and reformulate them into his own performances, attracted a broad audience. He was an expressive vocalist and a masterful guitar player, best remembered for his uptempo ragtime hits including "Step It Up and Go". At the same time he was capable of deeper material, and his versions of "Lost Lover Blues", "Rattlesnakin' Daddy" and "Mamie" are as deep as most Delta blues. Because of his popularity, he may have been overexposed on records, yet most of his songs remained close to tradition and much of his repertoire and style is kept alive by other Piedmont artists to this day.

DEATH

Fuller underwent a suprapubic cystostomy in July 1940 (probably an outcome of excessive drinking) but continued to require medical treatment. He died at his home in Durham, North Carolina on February 13, 1941 at 5:00 PM of pyemia due to an infected bladder, GI tract and perineum, plus kidney failure.

He was so popular when he died that his protégé Brownie McGhee recorded "The Death of Blind Boy Fuller" for the Okeh label, and then reluctantly began a short lived career as Blind Boy Fuller No. 2 so that Columbia Records could cash in on his popularity.

BURIAL LOCATION

Blind Boy Fuller's final resting place is Grove Hill Cemetery, located on private property in Durham, North Carolina. State records indicate that this was once an official cemetery, and Fuller's interment is recorded. The only remaining headstone is that of Mary Caston Langey. The funeral arrangements were handled by McLaurin Funeral Home of Durham, North Carolina, and the burial took place on February 15, 1941.

Blind Boy Fuller has been recognized on two different plaques in the City of Durham. The North Carolina Division of Archives and History plaque is located a few miles north of Fuller's gravesite, along Fayetteville St. in Durham. The City of Durham officially recognized Fuller on July 16, 2001, and the commemorating plaque is located along the American Tobacco Trail, adjacent to the property where Fuller's unmarked grave is located (several hundred feet east of Fayetteville St.).

Source: Wikipedia.

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Biography,

Blues,

Country blues,

East coast blues,

Folk-blues,

Piedmont blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Regional blues

Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil

Porto Alegre - Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Blind Willie McTell "Atlanta strut" (2004)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues,

Country blues,

East coast blues,

Piedmont blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Regional blues

Blind Willie McTell "The definitive Blind Willie McTell" (1994)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues,

Country blues,

East coast blues,

Piedmont blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Regional blues

Blind Willie McTell "Atlanta twelve string" (1992)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues,

Country blues,

East coast blues,

Piedmont blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Regional blues

Blind Willie McTell "Statesboro blues 1927-35" (2005)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues,

Country blues,

East coast blues,

Piedmont blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Regional blues

Blind Willie McTell

Among Atlanta’s early bluesmen, no one surpassed Blind Willie McTell,

who had it all – a shrewd mind, insightful lyrics, astounding

nimbleness on a 12-string guitar, and a sweet, plangent, and slightly

nasal voice. Sensitive, confident, and hip-talking, he was a beloved

figure in the various communities in which he traveled. He played

sublimely, a result of both natural talent and from performing hours a

day for people from all walks of life. McTell’s records reveal a

phenomenal repertoire of blues, ragtime, hillbilly music, spirituals,

ballads, show tunes, and original songs. His records seldom sound

high-strung or harrowed, projecting instead an exuberant, upbeat

personality and indomitable spirit.

Blind since infancy, Willie Samuel McTier was born in 1901 in the

Georgia cottonfield country nine miles south of Thomson and 37 miles

west of Augusta. His mother was Minnie Watkins, and his father has been

variously identified as Eddie McTier and McTear. (Evidently Willie

adapted the phonetic “McTell” spelling taught him in school.) One of

McTell’s earliest remembrances was of his mother singing hymns and

reading books to him. During his 1940 Library of Congress session,

McTell introduced his performance of “Just As Well Get Ready, You Got to

Die” by saying, “I will demonstrate how my mother and father used to

wander about their work. When they used to sing those old-fashioned

hymns. . . . Then you’d see ’em wanderin’ around the house, early in the

mornin’, cookin’ breakfast, tryin’ to get ready to go to the fields,

tryin’ to make some of the old country money. And way back in them days,

I hear one my own mother singed.” Relatives described Minnie Watkins as

an outstanding blues guitarist who began teaching her son 6-string

guitar when he was young. McTell may have played harmonica and accordion

first, and according to his first wife, Kate McTell, he was “also very

good on violin, but he didn’t like it. He just loved his guitar.” When

Willie was young, his father left the family.

McTell moved with his mother to Statesboro, some seventy miles to the southeast and the center of a prosperous lumber and turpentine industry. For a while they lived in a shack near the railroad tracks, and then moved into a small house on Elm Street. An older blind girl down the street encouraged McTell to seek an education, which he did. A family friend, Josephus “Seph” Stapleton, showed him some guitar. McTell’s father, whom he visited from time to time, also played. By his mid teens, McTell was performing in traveling shows and on the streets of Statesboro. In 1917, his mother remarried and gave birth to his half-brother, Robert Owens, for whom McTell always had a deep fondness. When their mother died in 1920, McTell returned to Thomson while Robert stayed with relatives in Statesboro. “After that I got on my own,” McTell recalled. “I could go anywhere I want without telling anybody where I was.”

During his 1940 Library of Congress session, McTell told John Lomax that from 1922 through ’25 he attended the State Blind School in Macon. There he learned to make brooms, work with clay and leather, and sew. (Later in life he’d make ashtrays, shoes, chairs, and pocketbooks.) He continued his education in private schools in New York City and Michigan, learning to read Braille books and sheet music. He reportedly had perfect pitch, as his half-brother Robert Owens claimed he could call out all the notes on a piano.

McTell became renowned for his unassailable sense of direction and extraordinary powers of perception and memory. He could hear the slightest whisper across a room, recognize hundreds of people by their voices, and navigate his way through city and countryside by using a tapping cane and a sort of personal sonar created by making a clucking sound with his tongue. Relatives described him as “earsighted.” In her 1975 interview with David Evans, published in Blues Unlimited, Kate McTell said, “He felt like he could see in his world just like we could see in our world. And he could tell you how long hair was, what color it was. And if you walked up to him and spoke to him, he could tell you whether you were a black person or a white person. And he could tell you how tall you were, or whether you were short – just by listening to your voice. And he could tell you whether you were a heavyset person or a thin person. He was marvelous. He could go anywhere he wanted to go. He had a stick, and he’d go ‘Tch, tch, tch, tch,’ to the sound of that. He’d never bump or run into anything.”

Photographs reveal that McTell favored Stella 12-strings throughout his career. Kate McTell recalled that he bought his guitars at a store on Decatur Street near Five Points. “He always liked the store. They would always tune it up, you know, and everything, and he’d take it out and tune it himself. And he could hit the box and tell whether it was any good or not. And he always bought his guitars there. If his guitar get to where he didn’t want to play it anymore, he would take it and trade it in or put it away and buy him another one. He’d never have ’em repaired.” He carried his guitar with him everywhere and treated it with great care. “He would never put his guitar in the back of nobody’s car,” Kate told Evans. “He’d always carry it on his back and hold it in his lap. He loved that guitar. He called it his baby.” At first McTell had used a bottleneck for slide, later switching to a metal ring or thimble. One of his neighbors told researcher Pete Lowry that McTell had “a bunch of bottlenecks in his coat pocket” and used different ones for different songs. He favored standard and open-G tunings and, unlike most other bluesmen in Atlanta, had a pronounced ragtime influence.

Blind Willie McTell launched his recording career in October 1927, cutting a pair of 78s during the Victor label’s field trip to Atlanta. After a pair of slideless blues, “Stole Rider Blues” and “Writin’ Paper Blues,” McTell recorded the first of many slide masterpieces, “Mama, Taint Long Fo’ Day,” working his bass and treble strings in a manner that had more in common with Texas gospel great Blind Willie Johnson than the Atlanta bluesmen. McTell signed a contract with Victor and a year later recorded two more 78s, including another masterwork, “Statesboro Blues.” While this song is best known today as Duane Allman’s signature bottleneck song with the Allman Brothers Band, the McTell version is slideless. And credit where credit is due: Duane Allman did not invent the “Statesboro Blues” slide figures – these were created by Jesse Ed Davis on an earlier cover on Taj Mahal’s 1967 debut album.

All of McTell’s initial Victor 78s were hardcore blues. In October 1929, he moonlighted for the first time with Columbia Records, which would release many of his more adventurous secular sides. McTell was in extraordinary form at his debut Columbia session, held in Atlanta. Among the four titles recorded on October 30th were two of his very best records, “Atlanta Strut” and “Travelin’ Blues.” In “Atlanta Strut” he sang of meeting up with a “gang of stags” and a little girl who looked “like a lump of lord have mercy,” and then embarked upon a lyrical journey that warps and mutates like a Dali painting. Meanwhile, his booming 12-string imitated a bass viol, cackling hen, crowing rooster, piano, slide guitar, even a man walking up the stairs! He fingerpicked “Travelin’ Blues” with extraordinary finesse, using his slider to mimic a train’s engine, bell, and whistle, and then doing a note-perfect chorus from “Poor Boy.” Columbia identified him on records as Blind Sammie, but for anyone who’d heard the Victor 78s, there was no mistaking who this artist was.

McTell was back recording for Columbia in April 1930, and the label promoted “Talking to Myself” with a newspaper ad. Columbia Records brought Blind Willie Johnson, the sublime Texas gospel slider, and his traveling companion, female singer Willie B. Harris, to Atlanta to record spiritual sides in April 1930. Reference books list McTell as playing at these sessions, but the 78s themselves reveal that Johnson is the only guitarist. It is certain, though, that McTell and Johnson became friends and toured together. As McTell told John Lomax in 1940, “Blind Willie Johnson was a personal pal of mine. He and I played together on many different parts of the states and different parts of the country from Maine to Mobile Bay.” McTell recalled that Johnson used a steel ring for slide and that the two of them enjoyed playing “I Got to Cross the River Jordan” together. When Lomax asked McTell if Johnson was a “good guitar picker,” McTell responded, “Excellent good!”

McTell’s next flurry of sessions took place in October 1931. On the 23rd, he cut the Columbia 78 “Talkin’ to Myself” b/w “Razor Ball,” and OKeh’s “Broke Down Engine” b/w “Southern Can Is Mine” He also backed Mary Willis on “Talkin’ to You Wimmen About the Blues” and three other songs. Curley Weaver, who’d become fast friends with McTell around 1930, accompanied him in the studio for the first time a week later. McTell, working as “Georgia Bill,” played unsurpassed ragtime-influenced 12-string on his unaccompanied “Georgia Rag,” while the 78’s flip side, “Low Rider’s Blues” featured Weaver soloing with a bottleneck as McTell shouted encouragement. The duo also backed Willis on her OKeh releases “Low Down Blues” and “Merciful Blues.” Perhaps a result of his performance with McTell, Weaver was invited back to record for OKeh on November 2, cutting duets of “Baby Boogie Woogie” and “Wild Cat Kitten” with singer Clarence Moore.

As the Depression deepened, blues record sales plummeted. For example, when “Travelin’ Blues” came out in 1930, it sold more than 4,200 copies, but when “Atlanta Blues” came out in May 1932, only 400 copies were manufactured. McTell’s “Southern Can Is Mine,” a gem of a performance, sold only 500 copies. McTell’s sole session of 1932 coupled him with another female singer, Ruby Glaze, and renamed him Hot Shot Willie. Their 78 of “Lonesome Day Blues” sold only 124 copies and is among his rarest records today. Meanwhile, sales of 78s by white musicians were much stronger: 78 Quarterly estimated that McTell’s Victor label mate Jimmie Rodgers’ “Mississippi River Blues” sold 47,355 copies and the Carter Family’s “On the Rock Where Moses Stood” sold 16,407.

Despite the discouraging sales, McTell’s luck at scoring record sessions held. In September 1933 he accompanied Curley Weaver and Buddy Moss to New York City for the marathon ARC session that, in hindsight, was the swansong of the early Atlanta blues guitar scene. McTell played second guitar on records credited to Curley Weaver and Buddy Moss, who in turn backed McTell on two-dozen gospel and blues selections. As David Evans writes in his excellent liner notes for the Columbia two-CD set The Definitive Blind Willie McTell, “Weaver’s work on second guitar, and occasionally second voice, is stunning throughout the session, whether he plays in slide style or fretting with his fingers. He is generally in a different key position or tuning from McTell and provides either a contrasting part or a more complex version of McTell’s part that cuts through the fuller sound of the 12-string. These tracks represent some of the high points in blues duet recording, ranking with the best pieces by the Beale Street Sheiks, Tommy Johnson and Charlie McCoy, or Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe.” McTell and Moss each recorded two versions of “Broke Down Engine” and covered Bumble Bee Slim’s “B and O Blues” at the session, with Weaver accompanying each of them. Moss remembered that McTell acted as their leader in New York, both at the session and in navigating subways. While the Moss and Weaver 78s came out on budget labels like Banner, Conqueror, Melotone, and Romeo, McTell’s dozen issued sides were on the premium Vocalion label. His “Don’t You See How This World Made a Change,” with Weaver adding guitar and vocals, came out credited to “Blind Willie and Partner.”

While McTell kept a home base in Atlanta during the early 1930s, he rambled far and wide. During summers, he played for vacationers in Miami and the Georgia Sea Islands. When the tobacco crop came in July and August, he’d play at warehouses and hotels around Statesboro and further east in Winston-Salem and Durham, North Carolina. He refused to accept car rides from strangers and almost always journeyed by train, bus, and trolley, confident in his ability to support himself by playing for tips in train cars, stations and depots, small clubs, and on the street. He acted as his own manager and agent, arranging bookings by telephone. He had strong networks of friends and relatives, especially around Thomson and Statesboro, where he returned often and was universally known by his childhood nicknames of “Doog” and “Blind Doogie.”

In Thomson, he enjoyed sitting under a relative’s tree and playing for friends and passersby. On weekends he’d entertain at picnics, juke joints, and house parties. His Sunday mornings were typically spent playing guitar at the Jones Grove Baptist Church. In Statesboro, McTell enjoyed visiting his half-brother Robert and a network of girlfriends, one of whom would chauffeur him around in an automobile he’d bought her. Statesboro residents recalled him playing ragtime, blues, and pop songs for ladies clubs, school assemblies, in front of hot dogs stands and hotels, and in the homes of whites and blacks alike. He played spiritual music at a couple of local churches, sometimes accompanying gospel quartets. He collaborated with many musicians in the area, especially an outstanding slide guitar player named Lord Randolph Byrd, who was known locally as Blind Lloyd and never recorded. The two traveled together to many Georgia towns, and they remained lifelong friends.

On January 10, 1934, Blind Willie McTell married Ruthy Kate Williams, a student he’d heard singing at a high school ceremony in Augusta. McTell was drawn to her strong, countrified voice, and it turned out their mothers had been friends and had jokingly promised their young children to each other. In her 1975 interview with David Evans, Kate McTell said that as newlyweds she and Willie moved into an apartment at 381 Houston Street N.W. in Atlanta. Curley Weaver and his longtime girlfriend, Cora Thomson, also moved in, and the two couples lived there for several years. Kate joined the choir at the Big Bethel A.M.E. Church, and her husband paid for her to attend college and earn a nursing degree. While she was in school, Kate told Evans, Willie was often on the road: “I said to Willie once, I said, ‘Willie,’ I said, ‘you got me stuck here in nursing school and you stay gone all the time.’ He said, ‘Baby, I was born a rambler. I’m gonna ramble until I die,’ he said, ‘but I’m preparing you to live after I’m gone.’ He did. He sure did.” Kate occasionally helped Willie with his songwriting, describing to David Evans, “He’d just think ’em up. And he’d come home and maybe give me a line or two to write. And then he’d say, ‘What did I tell you to write last night?’ I said, ‘Such and such a thing.’ He says, ‘Oh, well, this’ll be another one. Turn over to another page and write this down.’ The way he composed would be, write down words. Then we would sing ’em and see how they sound with the guitar. Sometimes he’d change ’em around.” She also remembered that he’d spontaneously create blues songs as he played.

On occasion, Kate sang spirituals with her husband and danced onstage when he played matinees at the 81 Theatre, sometimes with Curley Weaver sitting in. After seeing one such performance there in 1935, recording executive Mayo Williams invited the McTells and Weaver to Chicago to record for Decca Records. At these Chicago sessions, the McTells performed several old-time gospel slide tunes reminiscent of Blind Willie Johnson with Willie B. Harris. Weaver joined McTell on “Bell Street Blues” and several other secular tunes, finessing quick-fingered solos behind McTell’s 12-string bass parts and rhythm. McTell backed Weaver on a half-dozen blues as well, including a rare appearance on 6-string guitar on two of Weaver’s best records, “Oh Lawdy Mama” and “Tricks Ain’t Walking No More.” McTell was paid a hundred dollars per side – excellent pay during the Depression – although few of these records were issued at the time.

None of the records from his next session, held by Vocalion in Augusta in July 1936 with Piano Red, were issued. According to Kate, “They said he sang and played too loud. You know, he had a real loud voice. He thought he [Piano Red] was too high for his type of music. You see, Willie played a guitar, and the piano would drown the guitar out. And Willie couldn’t play with him. He couldn’t keep up with him, you know. He played so fast.”

For two summers, the McTells toured with a medicine show that featured a pair of blackface comedians and a barker who sold “rattlesnake liniment.” Kate’s role, she explained to Cheryl Evans, was to dance while her husband played: “I Charlestoned and Black Bottomed and tap danced. We did shows in Louisville, Kentucky, and we did a lot through Georgia, too, during the summer months when I wasn’t in school.” In the old minstrel tradition, the show’s comedians wore blackface. The troupe traveled by bus, train, and car, and McTell was paid a salary. Occasionally they’d set up a tent, but most of the time they performed outdoors in courthouse squares.

Around 1938, the McTells traveled to California and visited Oakland for a week. According to Kate, they stayed “where all the winos would be. I guess that’s what they called it. Anyway, I was real shocked to see people like that.” When Kate’s school was in session, McTell would often travel with Curley Weaver. “They were very good friends,” Kate recalled. “Willie would do most of the leading when they played together, and he was always the manager. He would always book the recordings or wherever they play at. And they would pay Willie, and then Willie would pay Curley.”

Eventually, the McTells moved to an apartment on Atlanta’s northeast side, near downtown. Kate recalled that Willie was particularly fond of collard greens, potatoes, and potato pie. They had a living room, kitchen, bedroom, and a music room where he stored his instruments. McTell especially enjoyed his music room, where he’d read Braille books from the library, take naps on his couch before going out to work, and enjoy a hot toddy before bed. He often played at Yates’ Drug Store on the corner of Butler and Auburn during the day, and spent his every evening serenading customers in parked cars at the Pig ’n’ Whistle, a drive-in barbecue joint on Ponce de Leon Avenue. As Kate explained to Cheryl Evans, “We call it a carhop. Different cars would call for him, you know. This car would say, ‘I want the musician over here.’ They’d say, ‘Well, I got him for an hour,’ or so long. And they would just pay him for that length of time. And then another car would call for him. He was paid by the peoples in the cars, and the Pig ’n’ Whistle paid him too. He would take requests, but he was just continually playing unless they requested certain songs.” On Saturdays, the McTells would perform at the 81 Theatre from 4:00 until 9:00, and then Willie would head over to the Pig ’n’ Whistle. On Sundays, the McTells occasionally performed at the Mt. Zion Baptist Church.

In one of the more fortuitous meetings in blues history, folklorist John Lomax and his wife found McTell wailing away at the Pig ’n’ Whistle in November 1940 and brought him to their hotel to record for the Library of Congress’ Archive of American Folk Song. On the drive to the hotel McTell called out directions and pointed to landmarks as if he could see them. This non-commercial session yielded a breathtaking array of folk ballads and spirituals, as well as a blues, a rag, a pop song, and insightful monologues on old songs, blues history, and life itself. “Dying Crapshooter’s Blues,” with its poetic imagery and ambitious arrangement, had been previously recorded by blueswomen in the 1920s. “Delia,” later covered by Johnny Cash, came out of the 19th-century ballad tradition.

McTell’s lonesome slide during the spirituals “I Got to Cross the River Jordan,” “Old Time Religion,” and “Amazing Grace” recalled Blind Willie Johnson’s 78s, especially in the way he’d use his slider to produce a string of notes and harmonic overtones from a single strike of the string. Lomax was aware of this connection, introducing “I Got to Cross the River Jordan” by saying, “This is a song played by Blind Willie McTell, which he says he used to sing and play with Blind Willie Johnson.” McTell quickly added, “This is a song that I’m gonna play that we all used to play in the country – an old jubilee melody.” Unlike Johnson, who played in open D, McTell played his version in open G capoed up two frets. McTell prefaced “Amazing Grace” by describing how it was played on banjo in the old-time churches of his youth. When he finished his instrumental performance, he said, “Now, that’s a song that our mothers and fathers used to hum back in the days when they’d be pickin’ cotton, pullin’ corn – farmer’s work.”

In less than an hour, McTell gave the American public some of the finest records he’d ever make. But the Library of Congress session did not go easily for McTell. One of the more telling exchanges between the folklorist and the bluesman occurred when Lomax asked McTell if he knew “any songs about colored people havin’ hard times here in the South . . . Complainin’ about the hard times and sometimes mistreatment of the whites. Have you got any songs that talk about that?” “No, sir,” McTell responded. “I haven’t, not at the present time, because the whites is mighty good to the Southern people, as far as I know.” Lomax pressed on: “‘Ain’t It Hard to Be a Nigger, Nigger’ – do you know that one?” “No,” McTell answered. “That’s not our time.” A moment later Lomax observed, “You keep movin’ around like you’re uncomfortable. What’s the matter, Willie?” McTell quickly shifted to another topic: “Well, I was in an automobile accident last night, little shook up. No one got hurt, but it was all jostled up mighty bad. Shake up – still sore from it, but no one got hurt.”

Not long after America entered World War II, Willie and Kate McTell separated. She moved to Augusta and became a Civil Service nurse, while Willie stayed in Atlanta and eventually began living with Helen Edwards, who took the name Helen McTell and stayed with Willie until her death in 1958. During the 1940s McTell began receiving assistance checks for his blindness and, without any record deals, mainly played house parties and at the Pig ’n’ Whistle. He continued to visit relatives in Statesboro, where he’d play at the Silver Moon, and Augusta, where Good Time Charlie’s tavern was a favorite venue.

While the jump blues of T-Bone Walker and other electric bluesmen had become a dominant sound on jukeboxes and radio broadcasts just after World War II, by the late 1940s the stripped-down, downhome music of John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and Lightnin’ Hopkins was beginning to attract an audience. In May 1949, an executive from the New Jersey-based Regal Records advertised on Atlanta’s black radio for country blues guitarists. Blind Willie McTell and Curley Weaver answered the call, cutting twenty blues and gospel selections for Fred Mendelshon at a studio on Edgewood Avenue. These excellent-sounding records reveal a wealth of innovative bass lines, interesting chords, masterfully fingerpicked solos, and sublime slide, especially on the songs McTell fronted. Their exciting “You Can’t Get That Stuff No More” revisited a 1932 Tampa Red hit, and McTell’s remakes of “Love Changin’ Blues” and “Savannah Women” featured sweet and low-down slide. “Pal of Mine” was a Tin Pan Alley pop song McTell had sung with medicine shows. Weaver, who played a 6-string at the session, recorded three selections with McTell’s support, singing with a strong voice on “Wee Midnight Hours,” “Brown Skin Woman,” and “I Keep on Drinkin’.” From this session, Regal issued only a few songs, although today they’re all available on the Biograph CD Pig ’n’ Whistle Red. On the issued 78s, “Hide Me in Thy Bosom” and “It’s My Desire” were credited to “Blind Willie,” and one of the blues songs identified him as “Pig ’n’ Whistle Red.”

Several months later, Weaver recorded two solo singles on acoustic guitar for the Sittin’ In With label, including spirited remakes of “Some Rainy Day” and “Tricks Ain’t Walkin’ No More.” These were his last recordings. He formed a trio with Buddy Moss and Johnnie Guthrie, playing around Georgia in the early 1950s, and then retired from music when his eyesight failed later in the decade. He died in 1962 and was buried in a rural churchyard in Almon, Georgia, where “Tricks Ain’t Walking No More” is etched beneath the name on his tombstone.

Blind Willie McTell’s next sessions took place during autumn 1949, when Ahmet Ertegun convinced him to make recordings for his fledgling Atlantic Records. “I had collected many recordings he had made for RCA Victor, and I thought I recognized his voice, but I wasn’t sure,” Ertegun wrote to filmmaker David Fulmer in 1992. “I asked him his name and discovered he was ‘the’ famous Blind Willie McTell. He spoke of having no interest in recording anything except religious music, and would only play the blues if I would release it under another name. Therefore, we decided on the pseudonym Barrelhouse Sammy. He was a charming, ebullient, but soft-mannered person.” For these Atlantic sessions, McTell reprised songs he’d recorded for Lomax – “Kill It Kid,” “Delia,” “Dying Crapshooter’s Blues” – as well as blues, a rag, and several spirituals played slide-style. With its thunderous bass runs and behind-the-bridge strums, McTell’s cover of “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie” almost sounded like prescient rock and roll. On subsequent listening to the acetates, though, Atlantic executives apparently deemed McTell’s solitary blues a thing of the past, and his sole Atlantic single, “Kill It Kid” backed with “Broke Down Engine Blues,” came out credited to “Barrelhouse Sammy (The Country Boy).” During the 1970s, most of the session was issued on the excellent Atlantic album Atlanta Twelve String. The hi-fi sound of these recordings is quite extraordinary. Steve Hoffman, renowned for his work remastering classic albums, explains how McTell was likely recorded: “I asked Tom Dowd about it. Tom didn’t record it, but he knew how it was done. He told me they used a portable Magnecord PT-6 full-track octal machine and a single RCA ribbon mike, a 77DX, and Scotch 112 tape. Sometimes the simple things in life are best.”

In 1950 McTell and Helen Edwards moved to 1003 Dimmock Street, the last residence he’d have in Atlanta. McTell began frequenting the Blue Lantern Club, an all-white restaurant on Ponce De Leon Avenue, performing tableside as well as in the parking lot. He sang tenor for the Glee Club of the Metropolitan Atlanta Association for the Colored Blind and played religious music on radio broadcasts from stations in Atlanta and Decatur. Around 1952 he acquired an electric guitar, but according to Kate, whom he’d visit once or twice a year, “He just liked his [acoustic] 12-string better, and he quit it.”

Overweight, drinking heavily, suffering from diabetes, and occasionally losing his balance, McTell seldom traveled beyond Atlanta, Thomson, and Statesboro in the mid 1950s, and he required hospital care from time to time. In September 1956, McTell made his final recordings for Ed Rhodes, who owned a record store on Peachtree Street near the Blue Lantern Club. McTell was supplied with corn liquor, and while he seemed to get looser as the session progressed, he played with drive and precision. McTell played all 18 selections without a slide, covering songs from his early days, his Library of Congress session, and his postwar sessions with Curley Weaver. He also covered pop songs, old blues by Blind Blake and the Hokum Boys, and hillbilly numbers such as “Wabash Cannonball,” telling Rhodes, “I jump ’em from other writers, but I arrange ’em my way.”

McTell quit playing blues soon afterward, when he got the calling to preach. He became a deacon at the Mt. Zion Baptist Church, using a Braille bible and dedicating himself to helping blind people. His health declined rapidly after his companion Helen died in November 1958, and in the spring of 1959 he suffered a stroke that caused partial paralysis. McTell’s cousin Eddie McTear moved him back to Thomson. That summer he suffered another stroke and was taken to the Milledgeville State Hospital, where he died from a cerebral hemorrhage on August 19,1959. Among the items in his estate were an acoustic 6-string guitar, three acoustic 12-strings, and an electric guitar and amplifier. McTell’s wish to be buried with one of his 12-string guitar was not honored, and due to a stonecarver’s error, his original tombstone read:

“Eddie McTier

1898

Aug 19 1959

At Rest”

Thirty years later, a proper gravestone and roadside historical marker were placed near Blind Willie McTell’s grave in the Jones Grove Baptist Church cemetery, seven miles south of Thomson. In 1983, Bob Dylan paid him tribute in his wonderful ballad “Blind Willie McTell,” singing, “Nobody can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell.” (This was issued on Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series 1-3.) A decade later, Dylan covered McTell’s “Broke Down Engine” and “Delia” on Love Gone Wrong.

While Blind Willie McTell, Curley Weaver, the Hicks brothers, Peg Leg Howell, and their prewar contemporaries created stacks of wonderful blues recordings, precious little of their influence resounds in modern music. Unlike their contemporaries in Chicago and Mississippi, their sound did not become a cornerstone of postwar blues and rock and roll, but rather a glimpse back at a bygone era. Fortunately, virtually everything they recorded is now available on CD, and much of it sounds just as remarkable and exhilarating as when first recorded. And today, many Georgia blues artists, some descendents of the original bluesmen, keep their songs alive on stage and record.

Source: Jas Obrecht Music Archive.

McTell moved with his mother to Statesboro, some seventy miles to the southeast and the center of a prosperous lumber and turpentine industry. For a while they lived in a shack near the railroad tracks, and then moved into a small house on Elm Street. An older blind girl down the street encouraged McTell to seek an education, which he did. A family friend, Josephus “Seph” Stapleton, showed him some guitar. McTell’s father, whom he visited from time to time, also played. By his mid teens, McTell was performing in traveling shows and on the streets of Statesboro. In 1917, his mother remarried and gave birth to his half-brother, Robert Owens, for whom McTell always had a deep fondness. When their mother died in 1920, McTell returned to Thomson while Robert stayed with relatives in Statesboro. “After that I got on my own,” McTell recalled. “I could go anywhere I want without telling anybody where I was.”

During his 1940 Library of Congress session, McTell told John Lomax that from 1922 through ’25 he attended the State Blind School in Macon. There he learned to make brooms, work with clay and leather, and sew. (Later in life he’d make ashtrays, shoes, chairs, and pocketbooks.) He continued his education in private schools in New York City and Michigan, learning to read Braille books and sheet music. He reportedly had perfect pitch, as his half-brother Robert Owens claimed he could call out all the notes on a piano.

McTell became renowned for his unassailable sense of direction and extraordinary powers of perception and memory. He could hear the slightest whisper across a room, recognize hundreds of people by their voices, and navigate his way through city and countryside by using a tapping cane and a sort of personal sonar created by making a clucking sound with his tongue. Relatives described him as “earsighted.” In her 1975 interview with David Evans, published in Blues Unlimited, Kate McTell said, “He felt like he could see in his world just like we could see in our world. And he could tell you how long hair was, what color it was. And if you walked up to him and spoke to him, he could tell you whether you were a black person or a white person. And he could tell you how tall you were, or whether you were short – just by listening to your voice. And he could tell you whether you were a heavyset person or a thin person. He was marvelous. He could go anywhere he wanted to go. He had a stick, and he’d go ‘Tch, tch, tch, tch,’ to the sound of that. He’d never bump or run into anything.”

Photographs reveal that McTell favored Stella 12-strings throughout his career. Kate McTell recalled that he bought his guitars at a store on Decatur Street near Five Points. “He always liked the store. They would always tune it up, you know, and everything, and he’d take it out and tune it himself. And he could hit the box and tell whether it was any good or not. And he always bought his guitars there. If his guitar get to where he didn’t want to play it anymore, he would take it and trade it in or put it away and buy him another one. He’d never have ’em repaired.” He carried his guitar with him everywhere and treated it with great care. “He would never put his guitar in the back of nobody’s car,” Kate told Evans. “He’d always carry it on his back and hold it in his lap. He loved that guitar. He called it his baby.” At first McTell had used a bottleneck for slide, later switching to a metal ring or thimble. One of his neighbors told researcher Pete Lowry that McTell had “a bunch of bottlenecks in his coat pocket” and used different ones for different songs. He favored standard and open-G tunings and, unlike most other bluesmen in Atlanta, had a pronounced ragtime influence.

Blind Willie McTell launched his recording career in October 1927, cutting a pair of 78s during the Victor label’s field trip to Atlanta. After a pair of slideless blues, “Stole Rider Blues” and “Writin’ Paper Blues,” McTell recorded the first of many slide masterpieces, “Mama, Taint Long Fo’ Day,” working his bass and treble strings in a manner that had more in common with Texas gospel great Blind Willie Johnson than the Atlanta bluesmen. McTell signed a contract with Victor and a year later recorded two more 78s, including another masterwork, “Statesboro Blues.” While this song is best known today as Duane Allman’s signature bottleneck song with the Allman Brothers Band, the McTell version is slideless. And credit where credit is due: Duane Allman did not invent the “Statesboro Blues” slide figures – these were created by Jesse Ed Davis on an earlier cover on Taj Mahal’s 1967 debut album.

All of McTell’s initial Victor 78s were hardcore blues. In October 1929, he moonlighted for the first time with Columbia Records, which would release many of his more adventurous secular sides. McTell was in extraordinary form at his debut Columbia session, held in Atlanta. Among the four titles recorded on October 30th were two of his very best records, “Atlanta Strut” and “Travelin’ Blues.” In “Atlanta Strut” he sang of meeting up with a “gang of stags” and a little girl who looked “like a lump of lord have mercy,” and then embarked upon a lyrical journey that warps and mutates like a Dali painting. Meanwhile, his booming 12-string imitated a bass viol, cackling hen, crowing rooster, piano, slide guitar, even a man walking up the stairs! He fingerpicked “Travelin’ Blues” with extraordinary finesse, using his slider to mimic a train’s engine, bell, and whistle, and then doing a note-perfect chorus from “Poor Boy.” Columbia identified him on records as Blind Sammie, but for anyone who’d heard the Victor 78s, there was no mistaking who this artist was.

McTell was back recording for Columbia in April 1930, and the label promoted “Talking to Myself” with a newspaper ad. Columbia Records brought Blind Willie Johnson, the sublime Texas gospel slider, and his traveling companion, female singer Willie B. Harris, to Atlanta to record spiritual sides in April 1930. Reference books list McTell as playing at these sessions, but the 78s themselves reveal that Johnson is the only guitarist. It is certain, though, that McTell and Johnson became friends and toured together. As McTell told John Lomax in 1940, “Blind Willie Johnson was a personal pal of mine. He and I played together on many different parts of the states and different parts of the country from Maine to Mobile Bay.” McTell recalled that Johnson used a steel ring for slide and that the two of them enjoyed playing “I Got to Cross the River Jordan” together. When Lomax asked McTell if Johnson was a “good guitar picker,” McTell responded, “Excellent good!”

McTell’s next flurry of sessions took place in October 1931. On the 23rd, he cut the Columbia 78 “Talkin’ to Myself” b/w “Razor Ball,” and OKeh’s “Broke Down Engine” b/w “Southern Can Is Mine” He also backed Mary Willis on “Talkin’ to You Wimmen About the Blues” and three other songs. Curley Weaver, who’d become fast friends with McTell around 1930, accompanied him in the studio for the first time a week later. McTell, working as “Georgia Bill,” played unsurpassed ragtime-influenced 12-string on his unaccompanied “Georgia Rag,” while the 78’s flip side, “Low Rider’s Blues” featured Weaver soloing with a bottleneck as McTell shouted encouragement. The duo also backed Willis on her OKeh releases “Low Down Blues” and “Merciful Blues.” Perhaps a result of his performance with McTell, Weaver was invited back to record for OKeh on November 2, cutting duets of “Baby Boogie Woogie” and “Wild Cat Kitten” with singer Clarence Moore.

As the Depression deepened, blues record sales plummeted. For example, when “Travelin’ Blues” came out in 1930, it sold more than 4,200 copies, but when “Atlanta Blues” came out in May 1932, only 400 copies were manufactured. McTell’s “Southern Can Is Mine,” a gem of a performance, sold only 500 copies. McTell’s sole session of 1932 coupled him with another female singer, Ruby Glaze, and renamed him Hot Shot Willie. Their 78 of “Lonesome Day Blues” sold only 124 copies and is among his rarest records today. Meanwhile, sales of 78s by white musicians were much stronger: 78 Quarterly estimated that McTell’s Victor label mate Jimmie Rodgers’ “Mississippi River Blues” sold 47,355 copies and the Carter Family’s “On the Rock Where Moses Stood” sold 16,407.

Despite the discouraging sales, McTell’s luck at scoring record sessions held. In September 1933 he accompanied Curley Weaver and Buddy Moss to New York City for the marathon ARC session that, in hindsight, was the swansong of the early Atlanta blues guitar scene. McTell played second guitar on records credited to Curley Weaver and Buddy Moss, who in turn backed McTell on two-dozen gospel and blues selections. As David Evans writes in his excellent liner notes for the Columbia two-CD set The Definitive Blind Willie McTell, “Weaver’s work on second guitar, and occasionally second voice, is stunning throughout the session, whether he plays in slide style or fretting with his fingers. He is generally in a different key position or tuning from McTell and provides either a contrasting part or a more complex version of McTell’s part that cuts through the fuller sound of the 12-string. These tracks represent some of the high points in blues duet recording, ranking with the best pieces by the Beale Street Sheiks, Tommy Johnson and Charlie McCoy, or Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe.” McTell and Moss each recorded two versions of “Broke Down Engine” and covered Bumble Bee Slim’s “B and O Blues” at the session, with Weaver accompanying each of them. Moss remembered that McTell acted as their leader in New York, both at the session and in navigating subways. While the Moss and Weaver 78s came out on budget labels like Banner, Conqueror, Melotone, and Romeo, McTell’s dozen issued sides were on the premium Vocalion label. His “Don’t You See How This World Made a Change,” with Weaver adding guitar and vocals, came out credited to “Blind Willie and Partner.”

While McTell kept a home base in Atlanta during the early 1930s, he rambled far and wide. During summers, he played for vacationers in Miami and the Georgia Sea Islands. When the tobacco crop came in July and August, he’d play at warehouses and hotels around Statesboro and further east in Winston-Salem and Durham, North Carolina. He refused to accept car rides from strangers and almost always journeyed by train, bus, and trolley, confident in his ability to support himself by playing for tips in train cars, stations and depots, small clubs, and on the street. He acted as his own manager and agent, arranging bookings by telephone. He had strong networks of friends and relatives, especially around Thomson and Statesboro, where he returned often and was universally known by his childhood nicknames of “Doog” and “Blind Doogie.”

In Thomson, he enjoyed sitting under a relative’s tree and playing for friends and passersby. On weekends he’d entertain at picnics, juke joints, and house parties. His Sunday mornings were typically spent playing guitar at the Jones Grove Baptist Church. In Statesboro, McTell enjoyed visiting his half-brother Robert and a network of girlfriends, one of whom would chauffeur him around in an automobile he’d bought her. Statesboro residents recalled him playing ragtime, blues, and pop songs for ladies clubs, school assemblies, in front of hot dogs stands and hotels, and in the homes of whites and blacks alike. He played spiritual music at a couple of local churches, sometimes accompanying gospel quartets. He collaborated with many musicians in the area, especially an outstanding slide guitar player named Lord Randolph Byrd, who was known locally as Blind Lloyd and never recorded. The two traveled together to many Georgia towns, and they remained lifelong friends.

On January 10, 1934, Blind Willie McTell married Ruthy Kate Williams, a student he’d heard singing at a high school ceremony in Augusta. McTell was drawn to her strong, countrified voice, and it turned out their mothers had been friends and had jokingly promised their young children to each other. In her 1975 interview with David Evans, Kate McTell said that as newlyweds she and Willie moved into an apartment at 381 Houston Street N.W. in Atlanta. Curley Weaver and his longtime girlfriend, Cora Thomson, also moved in, and the two couples lived there for several years. Kate joined the choir at the Big Bethel A.M.E. Church, and her husband paid for her to attend college and earn a nursing degree. While she was in school, Kate told Evans, Willie was often on the road: “I said to Willie once, I said, ‘Willie,’ I said, ‘you got me stuck here in nursing school and you stay gone all the time.’ He said, ‘Baby, I was born a rambler. I’m gonna ramble until I die,’ he said, ‘but I’m preparing you to live after I’m gone.’ He did. He sure did.” Kate occasionally helped Willie with his songwriting, describing to David Evans, “He’d just think ’em up. And he’d come home and maybe give me a line or two to write. And then he’d say, ‘What did I tell you to write last night?’ I said, ‘Such and such a thing.’ He says, ‘Oh, well, this’ll be another one. Turn over to another page and write this down.’ The way he composed would be, write down words. Then we would sing ’em and see how they sound with the guitar. Sometimes he’d change ’em around.” She also remembered that he’d spontaneously create blues songs as he played.

On occasion, Kate sang spirituals with her husband and danced onstage when he played matinees at the 81 Theatre, sometimes with Curley Weaver sitting in. After seeing one such performance there in 1935, recording executive Mayo Williams invited the McTells and Weaver to Chicago to record for Decca Records. At these Chicago sessions, the McTells performed several old-time gospel slide tunes reminiscent of Blind Willie Johnson with Willie B. Harris. Weaver joined McTell on “Bell Street Blues” and several other secular tunes, finessing quick-fingered solos behind McTell’s 12-string bass parts and rhythm. McTell backed Weaver on a half-dozen blues as well, including a rare appearance on 6-string guitar on two of Weaver’s best records, “Oh Lawdy Mama” and “Tricks Ain’t Walking No More.” McTell was paid a hundred dollars per side – excellent pay during the Depression – although few of these records were issued at the time.

None of the records from his next session, held by Vocalion in Augusta in July 1936 with Piano Red, were issued. According to Kate, “They said he sang and played too loud. You know, he had a real loud voice. He thought he [Piano Red] was too high for his type of music. You see, Willie played a guitar, and the piano would drown the guitar out. And Willie couldn’t play with him. He couldn’t keep up with him, you know. He played so fast.”

For two summers, the McTells toured with a medicine show that featured a pair of blackface comedians and a barker who sold “rattlesnake liniment.” Kate’s role, she explained to Cheryl Evans, was to dance while her husband played: “I Charlestoned and Black Bottomed and tap danced. We did shows in Louisville, Kentucky, and we did a lot through Georgia, too, during the summer months when I wasn’t in school.” In the old minstrel tradition, the show’s comedians wore blackface. The troupe traveled by bus, train, and car, and McTell was paid a salary. Occasionally they’d set up a tent, but most of the time they performed outdoors in courthouse squares.

Around 1938, the McTells traveled to California and visited Oakland for a week. According to Kate, they stayed “where all the winos would be. I guess that’s what they called it. Anyway, I was real shocked to see people like that.” When Kate’s school was in session, McTell would often travel with Curley Weaver. “They were very good friends,” Kate recalled. “Willie would do most of the leading when they played together, and he was always the manager. He would always book the recordings or wherever they play at. And they would pay Willie, and then Willie would pay Curley.”

Eventually, the McTells moved to an apartment on Atlanta’s northeast side, near downtown. Kate recalled that Willie was particularly fond of collard greens, potatoes, and potato pie. They had a living room, kitchen, bedroom, and a music room where he stored his instruments. McTell especially enjoyed his music room, where he’d read Braille books from the library, take naps on his couch before going out to work, and enjoy a hot toddy before bed. He often played at Yates’ Drug Store on the corner of Butler and Auburn during the day, and spent his every evening serenading customers in parked cars at the Pig ’n’ Whistle, a drive-in barbecue joint on Ponce de Leon Avenue. As Kate explained to Cheryl Evans, “We call it a carhop. Different cars would call for him, you know. This car would say, ‘I want the musician over here.’ They’d say, ‘Well, I got him for an hour,’ or so long. And they would just pay him for that length of time. And then another car would call for him. He was paid by the peoples in the cars, and the Pig ’n’ Whistle paid him too. He would take requests, but he was just continually playing unless they requested certain songs.” On Saturdays, the McTells would perform at the 81 Theatre from 4:00 until 9:00, and then Willie would head over to the Pig ’n’ Whistle. On Sundays, the McTells occasionally performed at the Mt. Zion Baptist Church.

In one of the more fortuitous meetings in blues history, folklorist John Lomax and his wife found McTell wailing away at the Pig ’n’ Whistle in November 1940 and brought him to their hotel to record for the Library of Congress’ Archive of American Folk Song. On the drive to the hotel McTell called out directions and pointed to landmarks as if he could see them. This non-commercial session yielded a breathtaking array of folk ballads and spirituals, as well as a blues, a rag, a pop song, and insightful monologues on old songs, blues history, and life itself. “Dying Crapshooter’s Blues,” with its poetic imagery and ambitious arrangement, had been previously recorded by blueswomen in the 1920s. “Delia,” later covered by Johnny Cash, came out of the 19th-century ballad tradition.

McTell’s lonesome slide during the spirituals “I Got to Cross the River Jordan,” “Old Time Religion,” and “Amazing Grace” recalled Blind Willie Johnson’s 78s, especially in the way he’d use his slider to produce a string of notes and harmonic overtones from a single strike of the string. Lomax was aware of this connection, introducing “I Got to Cross the River Jordan” by saying, “This is a song played by Blind Willie McTell, which he says he used to sing and play with Blind Willie Johnson.” McTell quickly added, “This is a song that I’m gonna play that we all used to play in the country – an old jubilee melody.” Unlike Johnson, who played in open D, McTell played his version in open G capoed up two frets. McTell prefaced “Amazing Grace” by describing how it was played on banjo in the old-time churches of his youth. When he finished his instrumental performance, he said, “Now, that’s a song that our mothers and fathers used to hum back in the days when they’d be pickin’ cotton, pullin’ corn – farmer’s work.”

In less than an hour, McTell gave the American public some of the finest records he’d ever make. But the Library of Congress session did not go easily for McTell. One of the more telling exchanges between the folklorist and the bluesman occurred when Lomax asked McTell if he knew “any songs about colored people havin’ hard times here in the South . . . Complainin’ about the hard times and sometimes mistreatment of the whites. Have you got any songs that talk about that?” “No, sir,” McTell responded. “I haven’t, not at the present time, because the whites is mighty good to the Southern people, as far as I know.” Lomax pressed on: “‘Ain’t It Hard to Be a Nigger, Nigger’ – do you know that one?” “No,” McTell answered. “That’s not our time.” A moment later Lomax observed, “You keep movin’ around like you’re uncomfortable. What’s the matter, Willie?” McTell quickly shifted to another topic: “Well, I was in an automobile accident last night, little shook up. No one got hurt, but it was all jostled up mighty bad. Shake up – still sore from it, but no one got hurt.”

Not long after America entered World War II, Willie and Kate McTell separated. She moved to Augusta and became a Civil Service nurse, while Willie stayed in Atlanta and eventually began living with Helen Edwards, who took the name Helen McTell and stayed with Willie until her death in 1958. During the 1940s McTell began receiving assistance checks for his blindness and, without any record deals, mainly played house parties and at the Pig ’n’ Whistle. He continued to visit relatives in Statesboro, where he’d play at the Silver Moon, and Augusta, where Good Time Charlie’s tavern was a favorite venue.