A small tribute to the works of valuable composers, musicians, players and poets. From Al Green and Alberta Hunter to Zoot Sims and Shemekia Copeland, among many others. Covering songs from styles as different as bluegrass, blues, classical, country, heavy metal, jazz, progressive, rock and soul music.

Friday, 6 January 2012

Bukka White "The Panama limited" (1971)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

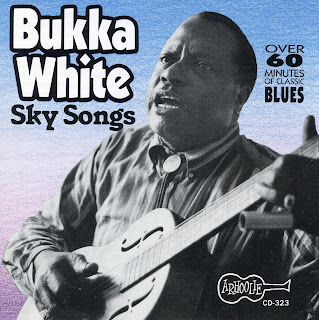

Bukka White "Sky songs" (1965)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

Bukka White "1963 isn't 1962" (1963)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

Bukka White "The complete sessions" (1930-40)

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

Bukka White

Bukka White

(true name: Booker T. Washington White) was born in Houston,

Mississippi (not Houston, Texas) in 1906 (not any date between 1902-1905

or 1907-1909, as is variously reported). He got his initial start in

music learning fiddle tunes from his father. Guitar instruction soon

followed, but White's

grandmother objected to anyone playing "that Devil music" in the

household; nonetheless, his father eventually bought him a guitar. When Bukka White

was 14 he spent some time with an uncle in Clarksdale, Mississippi and

passed himself off as a 21-year-old, using his guitar playing as a way

to attract women. Somewhere along the line, White came in contact with Delta blues legend Charley Patton, who no doubt was able to give Bukka White instruction on how to improve his skills in both areas of endeavor. In addition to music, White pursued careers in sport, playing in Negro Leagues baseball and, for a time, taking up boxing.

In 1930 Bukka White met furniture salesman Ralph Limbo, who was also a talent scout for Victor. White traveled to Memphis where he made his first recordings, singing a mixture of blues and gospel material under the name of Washington White. Victor only saw fit to release four of the 14 songs Bukka White recorded that day. As the Depression set in, opportunity to record didn't knock again for Bukka White until 1937, when Big Bill Broonzy asked him to come to Chicago and record for Lester Melrose. By this time, Bukka White had gotten into some trouble -- he later claimed he and a friend had been "ambushed" by a man along a highway, and White shot the man in the thigh in self defense. While awaiting trial, White jumped bail and headed for Chicago, making two sides before being apprehended and sent back to Mississippi to do a three-year stretch at Parchman Farm. While he was serving time, White's record "Shake 'Em on Down" became a hit.

Bukka White proved a model prisoner, popular with inmates and prison guards alike and earning the nickname "Barrelhouse." It was as "Washington Barrelhouse White" that White recorded two numbers for John and Alan Lomax at Parchman Farm in 1939. After earning his release in 1940, he returned to Chicago with 12 newly minted songs to record for Lester Melrose. These became the backbone of his lifelong repertoire, and the Melrose session today is regarded as the pinnacle of Bukka White's achievements on record. Among the songs he recorded on that occasion were "Parchman Farm Blues" (not to be confused with "Parchman Farm" written by Mose Allison and covered by John Mayall's Bluesbreakers and Blue Cheer, among others), "Good Gin Blues," "Bukka's Jitterbug Swing," "Aberdeen, Mississippi Blues," and "Fixin' to Die Blues," all timeless classics of the Delta blues. Then, Bukka disappeared -- not into the depths of some Mississippi Delta mystery, but into factory work in Memphis during World War II.

Bob Dylan recorded "Fixin' to Die Blues" on his 1961 debut Columbia album, and at the time no one in the music business knew who Bukka White was -- most figured a fellow who'd written a song like "Fixin' to Die" had to be dead already. Two California-based blues enthusiasts, John Fahey and Ed Denson, were more skeptical about this assumption, and in 1963 addressed a letter to "Bukka White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi." By chance, one of White's relatives was working in the Post Office in Aberdeen, and forwarded the letter to White in Memphis.

Things moved quickly from the time Bukka White met up with Fahey and Denson; by the end of 1963 Bukka White was already recording on contract with Chris Strachwitz and Arhoolie. White wrote a new song celebrating his good fortune entitled "1963 Isn't 1962 Blues" and swiftly recorded three albums of material for Strachwitz which the latter entitled Sky Songs, referring to White's habit of "reaching up and pulling songs out of the sky." Nonetheless, even White knew he couldn't get away with making up all his material regularly in performance, so he also studied his 78s and relearned all the songs he'd written for Lester Melrose. Although Bukka White was practically the same age as other survivors of the Delta and Memphis blues scenes of the 1920s and '30s, he didn't look like someone who belonged in a nursing home. White was a sharp dresser, in the prime of health, was a compelling entertainer and raconteur, and clearly enjoyed being the center of attention. He thrived on the folk festival and coffeehouse circuit of the 1960s.

By the '70s, however, Bukka White couldn't help getting a little bored with his celebrity status as an acoustic bluesman. White's tastes had grown with the times, and he would have loved to have played an electric guitar and fronted a band, as his old acquaintance Chester Burnett (aka Howlin' Wolf) and Bukka's own cousin, B. B. King, had been already doing successfully for years. But he only needed to look at what happened to his friend Bob Dylan's career for a lesson on what happens to folk blues artists who try and "go electric." So, Bukka White stayed on the festival circuit to the end of his days, beating the hell out of his National steel guitar, and sometimes his monologues would go on a little long, and sometimes his playing was a little more willfully eccentric than at others. Patrons would wait patiently to hear Bukka play "Parchman Farm Blues," although some of them were under the mistaken impression that they had paid their money to hear an artist who had originated a number that Eric Clapton made famous.

Blues purists will tell you that nothing Bukka White recorded after 1940 is ultimately worth listening to. This isn't accurate, nor fair. White was an incredibly compelling performer who gave up of more of himself in his work than many artists in any musical discipline. The Sky Songs albums for Arhoolie are an eminently rewarding document of Bukka's charm and candor, particularly in the long monologue "Mixed Water." "Big Daddy," recorded in 1974 for Arnold S. Caplin's Biograph label, likewise is a classic of its kind and should not be neglected.

Source: All Music.com.

In 1930 Bukka White met furniture salesman Ralph Limbo, who was also a talent scout for Victor. White traveled to Memphis where he made his first recordings, singing a mixture of blues and gospel material under the name of Washington White. Victor only saw fit to release four of the 14 songs Bukka White recorded that day. As the Depression set in, opportunity to record didn't knock again for Bukka White until 1937, when Big Bill Broonzy asked him to come to Chicago and record for Lester Melrose. By this time, Bukka White had gotten into some trouble -- he later claimed he and a friend had been "ambushed" by a man along a highway, and White shot the man in the thigh in self defense. While awaiting trial, White jumped bail and headed for Chicago, making two sides before being apprehended and sent back to Mississippi to do a three-year stretch at Parchman Farm. While he was serving time, White's record "Shake 'Em on Down" became a hit.

Bukka White proved a model prisoner, popular with inmates and prison guards alike and earning the nickname "Barrelhouse." It was as "Washington Barrelhouse White" that White recorded two numbers for John and Alan Lomax at Parchman Farm in 1939. After earning his release in 1940, he returned to Chicago with 12 newly minted songs to record for Lester Melrose. These became the backbone of his lifelong repertoire, and the Melrose session today is regarded as the pinnacle of Bukka White's achievements on record. Among the songs he recorded on that occasion were "Parchman Farm Blues" (not to be confused with "Parchman Farm" written by Mose Allison and covered by John Mayall's Bluesbreakers and Blue Cheer, among others), "Good Gin Blues," "Bukka's Jitterbug Swing," "Aberdeen, Mississippi Blues," and "Fixin' to Die Blues," all timeless classics of the Delta blues. Then, Bukka disappeared -- not into the depths of some Mississippi Delta mystery, but into factory work in Memphis during World War II.

Bob Dylan recorded "Fixin' to Die Blues" on his 1961 debut Columbia album, and at the time no one in the music business knew who Bukka White was -- most figured a fellow who'd written a song like "Fixin' to Die" had to be dead already. Two California-based blues enthusiasts, John Fahey and Ed Denson, were more skeptical about this assumption, and in 1963 addressed a letter to "Bukka White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi." By chance, one of White's relatives was working in the Post Office in Aberdeen, and forwarded the letter to White in Memphis.

Things moved quickly from the time Bukka White met up with Fahey and Denson; by the end of 1963 Bukka White was already recording on contract with Chris Strachwitz and Arhoolie. White wrote a new song celebrating his good fortune entitled "1963 Isn't 1962 Blues" and swiftly recorded three albums of material for Strachwitz which the latter entitled Sky Songs, referring to White's habit of "reaching up and pulling songs out of the sky." Nonetheless, even White knew he couldn't get away with making up all his material regularly in performance, so he also studied his 78s and relearned all the songs he'd written for Lester Melrose. Although Bukka White was practically the same age as other survivors of the Delta and Memphis blues scenes of the 1920s and '30s, he didn't look like someone who belonged in a nursing home. White was a sharp dresser, in the prime of health, was a compelling entertainer and raconteur, and clearly enjoyed being the center of attention. He thrived on the folk festival and coffeehouse circuit of the 1960s.

By the '70s, however, Bukka White couldn't help getting a little bored with his celebrity status as an acoustic bluesman. White's tastes had grown with the times, and he would have loved to have played an electric guitar and fronted a band, as his old acquaintance Chester Burnett (aka Howlin' Wolf) and Bukka's own cousin, B. B. King, had been already doing successfully for years. But he only needed to look at what happened to his friend Bob Dylan's career for a lesson on what happens to folk blues artists who try and "go electric." So, Bukka White stayed on the festival circuit to the end of his days, beating the hell out of his National steel guitar, and sometimes his monologues would go on a little long, and sometimes his playing was a little more willfully eccentric than at others. Patrons would wait patiently to hear Bukka play "Parchman Farm Blues," although some of them were under the mistaken impression that they had paid their money to hear an artist who had originated a number that Eric Clapton made famous.

Blues purists will tell you that nothing Bukka White recorded after 1940 is ultimately worth listening to. This isn't accurate, nor fair. White was an incredibly compelling performer who gave up of more of himself in his work than many artists in any musical discipline. The Sky Songs albums for Arhoolie are an eminently rewarding document of Bukka's charm and candor, particularly in the long monologue "Mixed Water." "Big Daddy," recorded in 1974 for Arnold S. Caplin's Biograph label, likewise is a classic of its kind and should not be neglected.

Source: All Music.com.

Labels:

Acoustic blues,

Blues revival,

Country blues,

Delta blues,

Pre-war blues,

Pre-war country blues,

Pre-war gospel blues,

Regional blues,

Slide guitar blues

Buena Vista Social Club "Buena Vista Social Club" (1997)

Labels:

Afro Cuban jazz,

Cuban jazz,

Cuban traditions,

Highly recommended,

Latin jazz,

Modern son,

Son,

World fusion

Buena Vista Social Club

Less a band than an assemblage of some of Cuba's most renowned musical forces, Buena Vista Social Club's origins lie with noted American guitarist Ry Cooder,

who in 1996 traveled to Havana to seek out a number of legendary local

musicians whose performing careers largely ended decades earlier with

the rise of Fidel Castro. Recruiting the long-forgotten likes of singer Ibrahim Ferrer, guitarists/singers Compay Segundo and Eliades Ochoa, and pianist Rubén González, Cooder entered Havana's Egrem Studios to record the album Buena Vista Social Club; the project was an unexpected commercial and critical smash, earning a Grammy and becoming the best-selling release of Cooder's long career. In 1998 he returned to Havana with percussionist son Joaquim to record a solo LP with Ferrer; the sessions were captured on film by director Wim Wenders, who also documented sell-out Buena Vista Social Club live performances in Amsterdam and New York City. (Wenders'

film, also titled simply Buena Vista Social Club, earned an Academy

Award nomination in 2000.) The public's continued interest in Cuban

music subsequently generated solo efforts from Segundo and González as well as a series of international live performances promoted under the Buena Vista Social Club aegis. A concert CD, At Carnegie Hall, drawn from the same triumphant show that Wenders featured in his documentary, was released in 2008.

Source: All Music.com.

Labels:

Afro Cuban jazz,

Cuban jazz,

Cuban traditions,

History,

Latin jazz,

Modern son,

Son,

World fusion

Buffalo Springfield "Buffalo Springfield again" (1967)

Labels:

Country-rock,

Folk rock,

Highly recommended,

Rock'n'roll

Buffalo Springfield

Apart from the Byrds,

no other American band had as great an impact on folk-rock and

country-rock -- really, the entire Californian rock sound -- than Buffalo Springfield. The group's formation is the stuff of legend: driving on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, Stephen Stills and Richie Furay spotted a hearse that Stills was sure belonged to Neil Young, a Canadian he had crossed paths with earlier. Indeed it was, and with the addition of fellow hearse passenger and Canadian Bruce Palmer on bass and ex-Dillard Dewey Martin on drums, the cluster of ex-folkys determined, as the Byrds had just done, to become a rock & roll band.

Buffalo Springfield wasn't together long -- they were an active outfit for just over two years, between 1967 and 1968 --but every one of their three albums was noteworthy. Their debut, including their sole big hit (Stills' "For What It's Worth"), established them as the best folk-rock band in the land barring the Byrds, though Springfield was a bit more folk and country oriented. Again, their second album found the group expanding their folk-rock base into tough hard rock and psychedelic orchestration, resulting in their best record. The group was blessed with three idiosyncratic, talented songwriters in Stills, Young, and Furay (the last of whom didn't begin writing until the second LP) yet they also had strong and often conflicting egos, particularly Stills and Young. The group, who held almost infinite promise, rearranged their lineup several times, Young leaving the group for periods and Palmer fighting deportation, until disbanding in 1968. Their final album clearly shows the group fragmenting into solo directions.

Eventually, the inter-personal tensions and creative battles led to a perhaps inevitable split, starting with Young's departure for a solo career. He would later reunite with Stephen Stills in Crosby, Stills, & Nash, joining the trio once a decade for various projects. In addition to CSN, Stills released solo albums and worked with a nother band, Manassas. Initially, Jim Messina and Richie Furay stayed together, forming the country-rock group Poco, but Messina left after three albums to team up in a duo with Kenny Loggins. Furay himself left Poco and teamed with Chris Hillman and JD Souther in the Souther Hillman Furay Band before pursuing a solo career. Rumors of a Buffalo Springfield reunion circulated for years -- Young even hinted at it with the song "Buffalo Springfield Again" -- but it never materialized.

Source: All Music.com.

Buffalo Springfield wasn't together long -- they were an active outfit for just over two years, between 1967 and 1968 --but every one of their three albums was noteworthy. Their debut, including their sole big hit (Stills' "For What It's Worth"), established them as the best folk-rock band in the land barring the Byrds, though Springfield was a bit more folk and country oriented. Again, their second album found the group expanding their folk-rock base into tough hard rock and psychedelic orchestration, resulting in their best record. The group was blessed with three idiosyncratic, talented songwriters in Stills, Young, and Furay (the last of whom didn't begin writing until the second LP) yet they also had strong and often conflicting egos, particularly Stills and Young. The group, who held almost infinite promise, rearranged their lineup several times, Young leaving the group for periods and Palmer fighting deportation, until disbanding in 1968. Their final album clearly shows the group fragmenting into solo directions.

Eventually, the inter-personal tensions and creative battles led to a perhaps inevitable split, starting with Young's departure for a solo career. He would later reunite with Stephen Stills in Crosby, Stills, & Nash, joining the trio once a decade for various projects. In addition to CSN, Stills released solo albums and worked with a nother band, Manassas. Initially, Jim Messina and Richie Furay stayed together, forming the country-rock group Poco, but Messina left after three albums to team up in a duo with Kenny Loggins. Furay himself left Poco and teamed with Chris Hillman and JD Souther in the Souther Hillman Furay Band before pursuing a solo career. Rumors of a Buffalo Springfield reunion circulated for years -- Young even hinted at it with the song "Buffalo Springfield Again" -- but it never materialized.

Source: All Music.com.

Labels:

Country-rock,

Folk rock,

History,

Psychedelic,

Rock'n'roll

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)